Diversity and inclusion in the workplace have been topical issues for some time. The Census Bureau recently announced that as early as 2045, the majority population in the United States will probably be nonwhite. The impact of this faster than expected, seismic demographic change in the United States has implications for society as a whole and for American businesses in particular.

Some industries have been quicker to adapt to the changes that an increasingly diverse population and customer base must invariably have on the makeup of their employee populations. Others, such as commercial and industrial real estate, have been less so, primarily due to long-held institutional practices that have had the unintended effect of limiting opportunities for talent that comes from nontraditional sources. That talent brings with it a wide range of life and work experience and embracing it goes beyond simply doing what’s right in a societal context. It is an increasingly strong business imperative.

It’s no longer news that companies with greater diversity among senior management are likely to be more profitable than their competitors. Women in Business: The Value of Diversity, a 2015 study of S&P 500 companies by Grant Thornton, found that American firms without female executives missed out on $567 billion in revenue in 2014. That was confirmed by additional reports, one in 2015 by McKinsey and Company and another, in 2016, from the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Then, in early 2018, McKinsey reported that, just as demographic changes were happening faster than expected, gender diversity in management increased profitability more than previously thought. In three short years the likelihood of companies in the top 25th percentile for gender diversity on their executive teams experiencing above-average profits went from 15% to 21%.

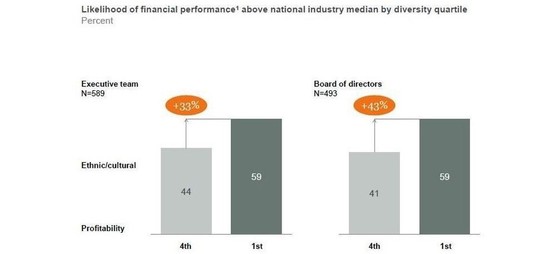

The impact on profitability goes beyond gender diversity. Companies with culturally and ethnically diverse executive teams are 33% more likely to see better-than-average profits and, at the board of directors’ level, 43%.

Another cultural shift that has been evident for some time will continue to make an impact on recruiting, hiring and retention practices. By late 2018, 56% of students on college campuses nationwide will be women, and that figure is projected to become 57% by 2026. Rising graduation rates across the board must be factored in, too. Between 1995 and 2015, the number of white 25-29-year-olds earning bachelors degrees had gone from 15% to 21%. It rose from 9% to 16% for Hispanics and, for Asians and Pacific Islanders, from 43% to 63%.

Commercial and industrial real estate is advancing to match other industries in terms of recruiting and hiring competent and diverse candidates. Colleges and universities have added degree programs in commercial real estate, funneling new graduates from heretofore underrepresented groups directly into the industry. These new hires’ demands and expectations are different from those of just one or two generations ago. Even with the increased number of candidates, degrees in hand and looking for work, employers will require awareness and genuine sensitivity to find this new talent.

“There’s going to be a war for talent,” says Herman E. Bulls, Vice Chairman, Americas, JLL and an African-American. “As we talk about what’s happening with the demographics of our nation, having a diverse organization is going to make you more capable of recruiting, attracting and retaining high-quality diverse talent, which will help you serve your market and your constituencies better.”

Where we are now

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, there is something of great divide between commercial and residential real estate where, for all practical purposes, there is parity between male and female brokers which also extends to the C-suites of large residential real estate companies. In fact, the three largest residential real estate brokerages in New York City, Douglas Elliman, the Corcoran Group and Halsted Property are all headed by female CEOs. In contrast, there is a notable scarcity of women in the upper ranks of the city’s commercial brokerages.

One traditional exception in commercial real estate is property management.

“We used to call property management ‘the pink ghetto’,” says Diana Scott, who until recently was Chief Human Resources Officer for Prologis, an international logistics company operating approximately 700,000,000 square feet of industrial space (She is now Chief of Human Resources with Guardian Life Insurance Company in New York City). “There was this weird thought that, ‘They are really good at it because they are women and they are customer-service oriented,’ but we debunked that. We had some very successful movement promoting from within our property management ranks and women and people of color were very successful as they transitioned into leasing and marketing.”

Another example of unintentional limitations that possibly spring from a mostly homogenous workforce was cited by both David Rogers, Vice President of Corporate Assets and Finance & Facility Management for Calares, formerly Brown Shoe, in St. Louis, Missouri; and Tirso A. Fernandez, Jr., Vice President, Commercial Real Estate for JP Morgan Chase.

“Even when we were considering building a new campus some of the developers and real estate professionals we work with automatically assumed that downtown was off the table,” Rogers, an African-American, says. “They wanted to get us further into the suburbs, but I think that firms with a more diverse representation wouldn’t be so quick to eliminate the city, or urban areas in general, as an option.”

Fernandez agrees. “People from diverse backgrounds and perspectives, I think, can have a clearer eye and look at things ― including opportunities ― more objectively,” he said. “Given my own personal experience and where I come from I can look at an opportunity in an area that somebody else might consider less desirable than midtown Manhattan or downtown Chicago or smack dab in the middle of San Francisco.”

This somewhat myopic worldview is certainly unintentional, and possibly the result of commercial real estate remaining something of an “old boys’ network” longer than other industries that were traditionally identified as such.

Rogers recounts a recent transaction in which he began the project with a senior manager of a major commercial real estate firm. At the next stage of negotiations the manager said to Rogers, “’Oh, let me introduce you to my son. He’s the one who’s going to be running this project next time.”

“And that’s not the first time that’s happened,” Rogers says. “It can create its own set of challenges when most of the industry is recruiting from people that they know, and not looking outward. But as the demographics of the country change that’s going to change. It has to.”

“Commercial real estate is absolutely a relationship business, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” says Scott. “But when those relationships get in the way of bringing new people into the fold that means that you’re not increasing the diversity of the organization and that becomes a problem.”

She also mentions long-established networks of college alumni and fraternities. “All of that becomes this fairway, this fluid, informal network. ‘Of course I’m going to help my friends in their careers, and I will help their kids, too,’ and there’s nothing wrong with that as long as they are also saying, ‘We also have to create a level playing field so that others have opportunities for positions within our company.”

Lydia Kennard, CEO of KDG Construction Consulting in Glendale, California, which she founded in 1980 as an offshoot of the architectural firm established by her father, African-American architect Robert Kennard, also spoke about the value of informal or familial relationships, and how the lack of opportunity to form those kinds of connections can present an obstacle to diverse candidates.

“It’s not just the racial identity, it’s also the ability to move through social organizations that can be impactful for your career,” she said. “Not that a lot of deals are made on the golf course, but if you can’t participate, you can’t play, and if you can’t play, you can’t win.”

And, finally, what may be at the very root of commercial real estate’s relative lack of diversity is that most potential employees of any underrepresented race, gender, ethnicity or orientation are simply unaware of the industry itself, much less opportunities that exist in it.

Historically, Bulls said, and especially in minority communities, “There is not a brightly lit line to commercial real estate. They may say, ‘Hey, I want to be a great basketball player,’ but not, “I want to be a great real estate guy!’ It just doesn’t happen because people just aren’t aware that it even exists, in many instances.”

The man on the street does not understand or have much knowledge about the construction or commercial real estate industries, Kennard said. “I was advantaged because my family was in the real estate and construction business, so I was exposed to it, but most people aren’t, especially women and people of color.

Rogers’ background is in accounting, and after surviving two rounds of layoffs in the banking industry, but not a third, he told a recruiter, “I will be in any industry except banking.” He landed an accounting position in the real estate department for a national retailer where, he said, “I initially had no interest in the other half of the house, focused on leases and growing the portfolio. But my natural curiosity made me want to hang out with those guys. For one thing, they were wearing much nicer suits than I was!”

From there, he adds, “just through expressing that interest they started to nurture an interest in real estate, and when opportunities arose, I capitalized on them.”

What’s Being Done

One primary driver of increased diversity is the increasing frequency with which clients and customers are asking for, and expecting, diverse teams.

“For any industry to remain viable the operators need to reflect the constituents that they serve,” Rogers said.

KDG serves a client base that is almost exclusively public and institutional and, Kennard said, “they are very diverse, so my employee base has to be reflective of my clients because it matters to them. I can’t just bring nondiverse candidates in senior leadership to my clients and hope that is going to sell well. And it’s not just the optics, but the commonality of experience and the business case is really clear: you’re not going to be able to get the cohort of talent unless you diversify the talent.”

“Let’s start with looking at the consumer,” Bulls says. “If you look at all the entities that must market to certain audiences I think it’s very, very important that those organizations make sure that they keep the feelings and concerns of all the particular stakeholders in mind. If the individual entities who are making hiring decisions, whether it is professional services, lawyers, engineers, or real estate professionals, tell these organizations, ‘I want your workforce to profile and represent and replicate my workforce or the market that I serve,’ then they will go out, look and find opportunities to make their workforces more diverse.”

Increasingly, diversity’s value is no longer perceived strictly in terms of race, gender, etc., but in also in terms of wider, and fresher perspectives that an organization can capitalize on to the benefit of all, including the company’s bottom line.

“People with the same educational and socio-economic backgrounds looking at the same thing are more likely to see the issue or the topic from the same lens, and you’re probably going to get the same answer from them,” Fernandez says. “I don’t think that’s a positive thing, and diversity of experiences and backgrounds and perspectives is critical to any business in this day and age.”

Rogers and Bulls echo that sentiment.

“As the population demographics change, the representation on the business side needs to change along with it. And diversity is not just about color, either,” Rogers says. “It’s easy to go to racial demographics, but I think that we also need diversity of thought when it comes to persons with disabilities and a workforce that includes millennials and baby boomers and everyone in between. If you have that diverse workforce you need the same diverse ideas within your management ranks.”

Bulls asks, “Are the clients that I represent at JLL all diverse? No, but quite a few of them are, and are they hiring me because I am diverse? Probably not, but if all things are equal and we have an opportunity to show that we have a diverse team, then I think we have a leg up, and that’s what a diverse member of the team brings to the table: attractiveness to a broader set of opportunities.”

“We need to make sure that we don’t get stuck in the mindset that what made us successful in the past will make us successful in the future,” Scott says. “We can’t become complacent. The driving force is getting different perspectives at the table, being open to different styles and different backgrounds.”

Affinity organizations exist on college campuses, within the industry and within individual companies, and several have been recognized for their efforts. Colliers International, Duke Realty and JLL have been recognized by the NAIOP Real Estate Development Association as exemplars of best practices for diversity and inclusion. Commercial Real Estate Women (CREW), the Urban Land Institute, the Building Owners Managers Association (BOMA), SmithGroup JJR, NAI Northern California, the Women’s Leadership Initiative, the Real Estate Associate Program (REAP) and Gilbane Building Company are actively working on initiatives to address, and increase, diversity and inclusion.

Bulls is co-founder of African American Real Estate Professionals, which now has chapters in Washington, DC, Boston, Atlanta, New York and Chicago. Rogers mentions Black MBAs and the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, and Fernandez touts the Toigo Foundation and Management Leadership 4 Tomorrow (ML4T), both geared towards people of color, as organizations that regularly serve as pipelines to the financial services and real estate industries and that he himself has tapped for talent.

Scott describes Prologis’ alignment with not only campus real estate groups, which tend to attract mostly young men, but with collegiate diversity groups, as well. “Especially those involved in studying business-oriented degrees, math, and economics to educate them about careers in real estate and why it is an exciting opportunity. We started to create demand, and I think that is partly what has to happen,” she said.

Both Scott and Kennard talk about the perhaps overlooked Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) as viable recruiting grounds.

“In addition to recruiting from our six or seven universities that we always had strong relationships with we also started going to some of the traditionally black universities, like Howard, Spellman and Morehouse and do some recruiting on their campuses and building some relationships,” Scott said.

And Kennard recounts an incident that was indicative of progress that still needs to be made, despite the ostensible awareness around diversity and inclusion. Someone at a meeting made a casual remark that implied some doubt about finding qualified candidates at HBCUs. “I had to challenge that,” she says. “To suggest that just because you go to a HBCU that you’re not of the same caliber as someone who went to Harvard or Yale is an inherent stereotype and bias, and it is absolutely wrong.”

Conclusion

Recruiting, hiring and retaining diverse talent requires expanding the parameters that have admittedly served the commercial and industrial real estate industry long and well, and it requires more of companies than mere awareness of the social and economic benefits of doing so. It requires true open-mindedness around life experiences, worldviews and potential talent.

Clients have always entered into partnerships with recruiting firms with a list of specific qualifications they expect to see in a short list of candidates. Education, years of experience, experience in a specific field, etc. have long been among the criteria voiced. A marked change has occurred when it comes to recruiting in the real estate space within the last few years, however.

Now, clients across the real estate spectrum, including retail, logistics, office, industrial and commercial, verbalize their interest in seeing diverse talent on the short list presented. Along with that request there is a clear expectation that one, if not two, diverse candidates end up on that slate and a palpable sense of disappointment if there is not.

There are three primary reasons for this evolution.

One is the realization by all stakeholders that there is a relatively untapped source of talent that is not only representative of current and ongoing demographic change, but with worldviews and life experiences that are needed for commercial real estate firms to remain relevant. That, in turn, leads directly to measurable value among competition and in the marketplace.

Secondly, forward-thinking firms are driven by not only the real dollars and cents benefits of embracing diversity. More just the right thing to do, it increases opportunities for employees and employers, both.

Finally, search firms are being asked to include diverse candidates because clients, themselves, are in turn being asked about their own diversity and inclusion practices. Most, if not all, industries are under pressure from their customers to offer a workforce that reflects their own and/or the markets they serve.

These new parameters must acknowledge that the next few generations of new hires bring with them an attitude of selectiveness around collaboration, flexibility in scheduling and accommodating life events, such as having children and prioritizing family. Those circumstances and life choices, though perhaps not as disruptive to a woman’s career path as they once were, nevertheless remain real concerns, and they are increasingly just as likely to be concerns for men, too.

It requires a willingness to embrace disruption for the greater good of all shareholders, and on a large scale.

“Disruption is going to happen all around us,” Scott says. “The question is: are you going to allow yourself to be disrupted, or are you going to be the disruptor? Bringing diverse perspectives to your company will help you be the disruptor of your own industry, and not the victim of it.”